The recent pandemic has swiftly exposed structural vulnerabilities across the world. In Australia, housing is a fundamental component of household wealth, with the housing market being central to our economic recovery. As time has shown, employment and the duration of unemployment levels is a pivotal factor in the economic recovery, while our robust financial system has provided structural integrity. With strong structural and regulatory foundations within our banking system, perhaps the lucky country is positioned well for COVID-19.

Time has shown that it is the reaction to a crisis that determines the eventual impact on the economy and society at large. The past 100 years has seen the Australian economy face many challenges, both global and domestic. However, the lessons learned have strengthened the foundations of our system to manage the resulting (systemic) risks and issues that follow.

As with most crises, they are difficult if not impossible to predict, and the recent pandemic is no exception. COVID-19 has rapidly swept across the world, forcing governments into swift (re)action to cushion the eventual economic impact, and contain the overall effect on the financial system.

Several factors are critical to ensuring a short duration cycle and a fast recovery: the health of the Australian housing market, unemployment and mortgage serviceability, government and policy responses, consumer and business confidence, and the underlying robustness of the banking sector foundations.

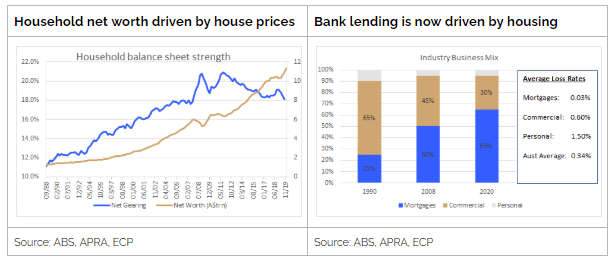

For Australia, the housing market is key to our economic recovery due to its importance to household wealth and its relative significance on banks’ balance sheets. The regulatory response has been directed to support financial stability, particularly regarding housing.

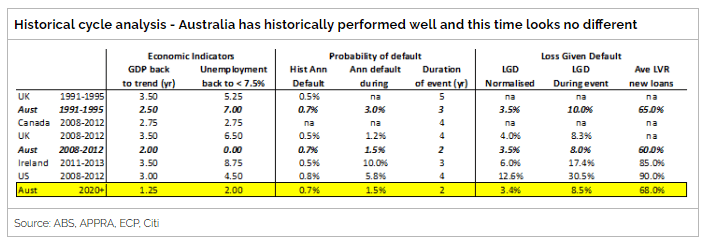

Unemployment and our labour market health play a pivotal role in our banking system. Rises in the unemployment rate above 7.5% correlate to increases in bad and doubtful debts as when people lose their jobs, their ability to repay their mortgages reduces. Aggressive policy responses from the Government, the RBA and APRA, squarely focus on ensuring that unemployment and the housing market is somewhat insulated from the economic downturn.

Through several historical cycles, banks have more robust funding and capital structures to ensure they can weather future downturns. When we overlay this with recent inquiries such as the Royal Commission, the Australian banking sector fundamentals appear robust.

While it is difficult to swim against the tide of the slowing global economy, the measures made to date significantly reduce the stress on the Australian economy, and we expect a shorter duration cycle. Below, we discuss historical events and key economic features that have provided for strong foundations as we battle the current pandemic crisis.

Is this time really different?

We are usually wary of comments that “this time it’s different”, so we instead ask ourselves, is this time really different? Here, it is essential to establish the differences between historical cycles and understand why the banks are in a better position to deal with the issues at hand.

There have been three major economic events over the past 30 years and each one of these has been very different in its impact on the banking sector:

The 1990 Recession was a global crisis driven by interest rate shocks and market meltdowns. Economies and markets were overheating, and Central Banks stepped in to curb inflation. Unemployment skyrocketed as consumer sentiment was crushed, with the key feature of this crisis being the length of time for recovery. In Australia, unemployment took seven years to fall below 7.5%, the level that has historically been considered “safe” in terms of mortgage-related stress.

The 2008 GFC was a financial markets liquidity crisis that flowed out into the broader economy. The rapid escalation of the US housing market, fuelled by sub-prime mortgage lending, provided the genesis for system collapse. While the impact was severe, the broader economic damage was (somewhat) contained, and the duration of the cycle was relatively short. In Australia, unemployment peaked at 5.6%, with our banking system proving to be resilient, providing robust economic foundations.

The 2020 Pandemic is a global health crisis stemming from COVID-19. Global markets and economies were relatively stable, leading into the crisis with modest consumer and business confidence. In Australia, recent financial service industry inquiries have improved responsible lending and capital requirements, building upon the strong foundations that have seen us through prior crises.

The closure of national borders and the complete shut-down of the global travel system is an event that nobody could have foreseen. Government has impacted global business activity through enforced lock-downs; an unprecedented economic experiment with extreme variability in potential economic outcomes. Governments, Regulators and Central Banks have been swift and effective. In Australia, unemployment has spiked, with most market commentators predicting a relatively short duration cycle and a strong recovery into 2021.

The duration of a cycle is perhaps the most critical feature when it comes to determining the overall economic impact. Longer duration cycles have a significant effect on the unemployment rate, driving bad and doubtful debts, putting downward pressure on housing prices. The Recession in the 1990s was the last long-duration cycle which saw unemployment rise above 12%, taking over seven years to fall back to manageable levels. With this in mind, one may be optimistic this time around.

Aussie Housing Market

Is Australia at risk?

Housing is of utmost importance for the Australian economy. For most Australians, a person’s home is a core part of their overall wealth. The increase in house prices over the decade has magnified this phenomenon, meaning the housing sector is even more critical.

The reliance on housing is a double-edged sword: it increases the economic risk related to house prices, yet it is positive for the banking sector. The banks are always willing to lend more into the mortgage market because the risk of default and loss is much lower than other loan categories.

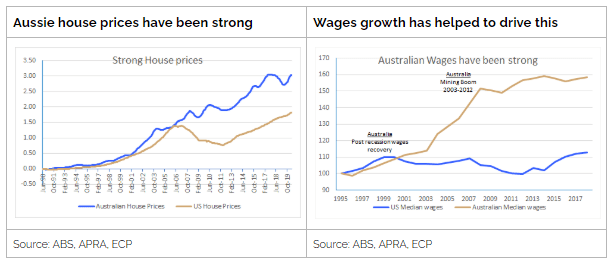

In Australia, house pricing has been unquestionably strong over the past 30 years, supported by material growth in wages. When comparing house prices in Australia to the US, Australia has outperformed due to a robust labour market and stable wages environment. The labour market has been the most critical aspect of the housing market, and this continues to be the case.

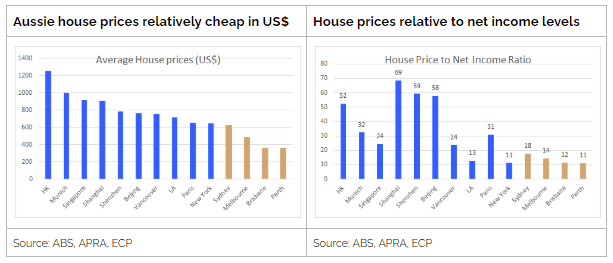

Australian house prices are reasonably valued in a global context

Australian house prices are reasonable when compared to major cities globally, both on a US dollar and price-to-net income basis. Lower interest rates, higher immigration rates, population growth and falling personal income tax rates over the next five years, is further supportive of long-term housing market valuations in Australia. Construction levels have also been slow to respond in Australia, so there is structurally a shortage of both single-family and multi-dwelling homes.

This time entry into the cycle is positive for the recovery

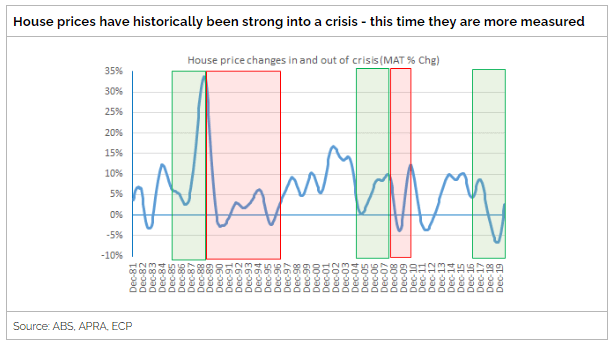

House price strength leading into the 1990s recession and the GFC created an exuberance reversal which added fuel to the economic downturn. The chart below highlights the relative peaks of house pricing, with varying degrees of post-crisis recovery being impacted by unemployment levels.

As we head into the current crisis, the banking sector has already been under considerable scrutiny regarding their lending practices. To date, slower credit lending and subdued house price growth over the past couple years has curtailed investor speculation and extreme house price pricing. Arguably, the housing market has rebased, potentially creating a more stable footing for supply and demand.

The Role of Unemployment

In Australia, the past three economic crises have seen a correlation between bad and doubtful debts and the unemployment rate. In the 1990s, significant commercial exposures drove bad and doubtful debts, while in 2008, the unemployment rate never rose above 7.5%, meaning bad and doubtful debts were relatively manageable. Here, the future direction of bad and doubtful debts and our broader housing and economic health will be driven by the unemployment rate and the duration of its elevation.

When considering the future of defaults, one must review historical default rates and loss rates to explore the drivers of why there were such significant increases in the past. Here, we compare Australia with the US to provide more colour surrounding the impact of defaults.

In 2008, the US market was the most notable example of high default rates and housing loss rates, reaching record highs. The lending practises in the US were unconstrained, with subprime mortgage lending relying less on individual income and expenses data or serviceability. Loan to Value (LVR) ratios increased to ~90% while housing prices reached record levels.

As unemployment began to rise, default rates accelerated, causing loss rates to accelerate, which compounded the problem of declining house prices. The duration of this economic slowdown was 4–5 years which meant a delayed recovery in housing and the economic impact was substantial.

The following charts show how high the default rates were in the US compared to Australia, which did not enter into subprime lending activities and also had a market where LVRs were much lower at around 60–70%.

The Impact of Policy

The policy response from the Government, RBA and regulators leading into this cycle has significantly assisted the banking sector in managing the flow-on effects of the pandemic. While the number of policy-related responses is vast, we discuss some key initiatives below.

In Australia, government policy has focused on 1) the employment market and the retention of jobs; 2) Providing relief to mortgages and SME loans; and 3) Other household relief designed to ensure that employment rates remain strong or those bad and doubtful debts stay to a minimum. To date, the policy measures have been hugely supportive, yet it is too early to predict the longer-term impact.

Some of the critical policies and changes from the Government, RBA and APRA that will be critical in ensuring the duration and impact of the downturn are lessened include:

Government: Deferments of SME and Mortgage repayments. JobKeeper wages subsidy package (and recent extensions). Direct household payments and other subsidies including childcare etc.

RBA: Multiple cuts to the cash rate — now sitting at 0.25%

APRA: Changes to the way banks deal with bad and doubtful debts associated with COVID related loans. Changes to the capital ratios and acceptance of a reduction in ratios during this time.

Banks: Adoption and extension or loan deferment policies from APRA and the Government have been adopted by the banks in order to assist households while smoothing short-term exposures.

Quality Foundations

Improved Capital Structures

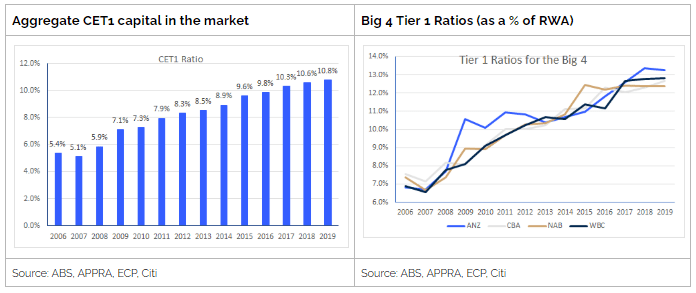

The capital structure of the Australian Banking system has improved significantly over the past 15 years, ensuring that the banks are well-positioned to weather any economic downturns or crisis.

The current capital structure is the result of two major events:1) The GFC and the effects upon US and European banks, and 2) the Murray Review which targeted foreign funding and the credit rating that Australian Banks have in the global funding marketplace.

The GFC exposed issues regarding inadequate capital structures which forced Governments to step in where the banks had failed. The Basel review found that European and US banks needed to have better measures limiting the reliance on Governments in future crises. While Australia fared relatively well during the GFC, it too adopted the new capital measures to be consistent with global practises.

In 2014, the Murray Review found that more loans are outstanding than domestic deposits or funding sources, meaning the Australian banks are reliant on global wholesale markets to fund their loan books. As a result, the review identified that the banking sector needs to be “unquestionably strong” and maintain its strong credit rating to ensure that the current funding sources are maintained and increased over time.

Further, any adverse changes to this (such as a house price collapse) would be catastrophic for the sector and the banks’ ability to lend money to households. As a result, the focus on capital ratios increased, and the average Tier 1 capital now sits well above the target range of 10.5%.

Why are banks stronger this time around?

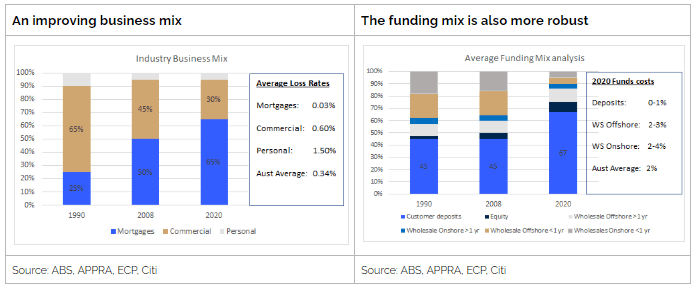

In 2020, the economy and the banks are in a better financial position to weather the current economic crisis. When compared to previous cycles, two key factors will help to ensure there is less impact on the sector in general — a better business mix and a better funding mix.

In terms of the business mix, the Australian banking system is in much better shape than previous cycles. Bank lending (generally) comprises home lending or mortgages, and non-house lending of commercial and business loans.

Mortgages are large in number, small in value and are secured by the underlying property. The LVR is essential when assessing default risk in mortgages because ultimately, it determines what portion of the loan is recoverable in the event of default and downward house pricing pressure. In Australia, LVRs are low at around 60–70%, meaning the risk of losses is lower.

Commercial and business loans can also be significant in numbers and small in value. Still, they tend to have a mix of substantial corporate style loans that can often have industry concentration risk associated with them. The security behind these loans can often be difficult or more complicated to identity and value. In the event of economic crisis and subsequent default, the ability to fully recover these loans is difficult. Currently, the most notable ongoing example is Virgin Airlines.

In terms of the funding mix, the major banks have materially improved since prior crises with a high proportion of funding being from local retail deposits — a safer option given Government guarantees to deposit holders and also being the cheapest source in the market.

Looking Forward

What about deferred loans?

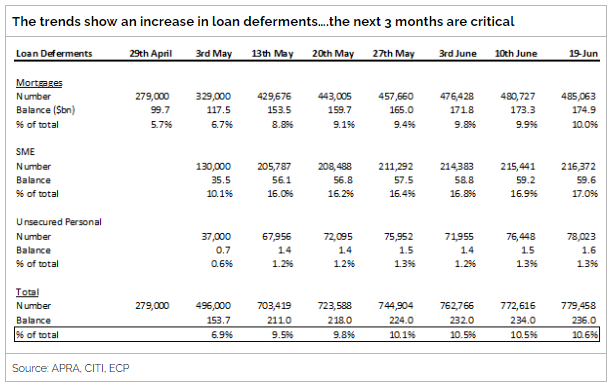

Deferments of loans at this stage are running at around 10% of total Mortgages and 16–17% of total SME related loans. It is critical to determine how these loans are to be treated in the future. There are three categories of loans that need to be addressed going forward and it should be noted that the situation, especially in Victoria is very fluid and changing all the time right now:

Unrepaid loans are situations where individuals have lost their jobs with no prospect of re-entering the workforce. Their ability to service their mortgages once the loan resumes is unfeasible, and resultantly, banks write off these loans. Around 2% of loans fit into this category and will be advanced from Stage 1 to Stage 3 provisioning.

Extended payment terms are situations where people have experienced a reduction in income, or they may have lost their jobs. Still, the ability to regain employment is reasonably likely within 12 months. Here, the legislation permits the banks to roll over loans and capitalise the interest while allowing a repayment holiday. These ‘hardship provisions’ are a relatively new concept and assist banks in smoothing out their overall loss exposure. Approximately 3% of loans fit into this category and will transition from Stage 1 to Stage 2 provisioning.

Nonessential deferrals where individuals who might have experienced a reduction in income or no real change at all or they may have had their incomes subsidised by specific government programs. These people will be able to continue repaying their loans, and they will start to do so once the deferment plans rollover. Approximately 5% of loans fit into this bucket and are expected to return to normal in September or March.

Implications for the Banks as we head into 2021

While the extent of the economic hardship to be faced and the duration of the cycle is hard to predict, the Australian Banking system appears well prepared to navigate the current pandemic crisis, which will benefit the economy and households alike as we move into a recovery phase.

Today, the business mix has (positively) changed since the early 1990s. A shift away from commercial and business loans to mortgages has lowered the risk profile and loss rate — resulting in a far superior position to deal with the current crisis. Mortgage defaults have historically been much lower than commercial or business loan defaults, and they are also easier to manage in a down cycle.

Broadly, the ‘Big Four’ banks are well-positioned in terms of their business and funding mix, improved capital structures and the policies that the Government is putting in place. It is still unclear how the eventual bad and doubtful debts will play out; however, the regulatory response will help to facilitate a smooth transition in support of the broader economy.

In our view, CBA is the best placed of the major banks given their robust capital and funding structures and their dominant position in the mortgage market. The company has successfully taken market share over the past year. While all banks will experience a period of earnings suppression, we believe they will come out of this crisis well-positioned for longer-term growth.

The article has been prepared by ECP Asset Management Pty Ltd (ECP). ECP is a funds management firm based in Sydney, Australia. For further information, visit www.ecpam.com. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for financial advice. ECP and the analyst own shares in Commonwealth Bank of Australia. ABN 26 158 827 582, AFSL 421704, CAR 44198.