Block - Part 3: The Convergence of Money and Commerce

Introducing Retail Merchants to Cash App

Having looked backward to understand how Block grew Square into a US$150bn payments business (part one) and applied these learnings to scale Cash App into an 80 million US consumer fintech (part two), we now explore the opportunities ahead. We believe the connection of commerce (merchants) and money (consumers) has the potential to create significant value.

In 2022, Block launched Cash App ‘Commerce’ in the US. This is its first step towards creating a low-cost flow of funds between a consumer and merchant’s bank, which has numerous implications for the unit economics of those transactions, discussed below. The initial release is a simple directory for Cash App consumers to discover merchants accepting Cash App Pay. However, we expect creative innovation to follow.

The big opportunity, in our view, is for Block to charge merchants a channel fee in addition to those earned via ordinary payment facilitation (or merchant acquiring), and to earn the right to do so by having captive consumers that start their shopping journey inside of Cash App’s Commerce marketplace. The ability to control the flow of consumer demand could position Cash App at the top of the commerce funnel.

The key question, therefore, is how could Block turn Commerce into a place consumers begin their shopping journey? Block needs to solve this problem to compete with established shopping journeys at merchants directly (knowing what you want), Amazon (free delivery, reviews and trusted pricing), and Google (search discovery).

We believe there are two answers - financial benefits and personalised commerce - and we see Cash App having the ingredients at its disposal to bring both to the consumer.

Reason #1: Consumer Financial Benefits

History is filled with scaled two-sided payment networks that arose from providing a customer utility which aggregated demand and attracted paying merchants into the network.

Diners Club and AMEX are the original examples of closed-loop financial networks, dating back to the 1950s. They used a financial benefit (the credit card) to aggregate consumer demand and charge merchants a premium payment processing fee (now known as interchange) to participate in the network.

In the 2000s, PayPal leveraged the utility of trusted eCommerce payments to build dominant global merchant acceptance. More recently, Afterpay showed that by flipping the credit model on its head with fee-free credit instalments, a scaled consumer-merchant network could be built.

Today, Cash App has 80 million annual active users in the US. Initially focused on peer-to-peer money transfers, Cash App expanded its suite of services to increasingly emulate those provided by traditional bank accounts, moving closer towards its vision of redefining the world's relationship with money.

With the launch of Cash App Borrow, Cash App BNPL, budgeting tools, tax filings, cash and cheque deposits, a subset of users are increasingly utilising Cash App as their main financial account.

Many of these tools could be directed - exclusively or preferentially - toward transactions that occur within the Commerce interface.

It's not difficult to envision Cash App Borrow or BNPL being available for transactions exclusively within Commerce, while shopping enhancement features like digital layaway ('hold that sales price for me') could be linked to a savings goal as a reward for financially disciplined consumers unwilling to use credit for larger purchases but equally unwilling to miss rare one-time retail discounts.

By focusing access to these financial tools toward transactions inside Commerce, consumers would have a reason to begin their shopping journey with Cash App.

Thereafter, loyalty rewards can offer additional financial incentives to shop via Commerce. Cash App does this today with its Boost Rewards feature, which provides customers with instant product discounts. We believe this could be turbo-charged by the added funding from channel fees.

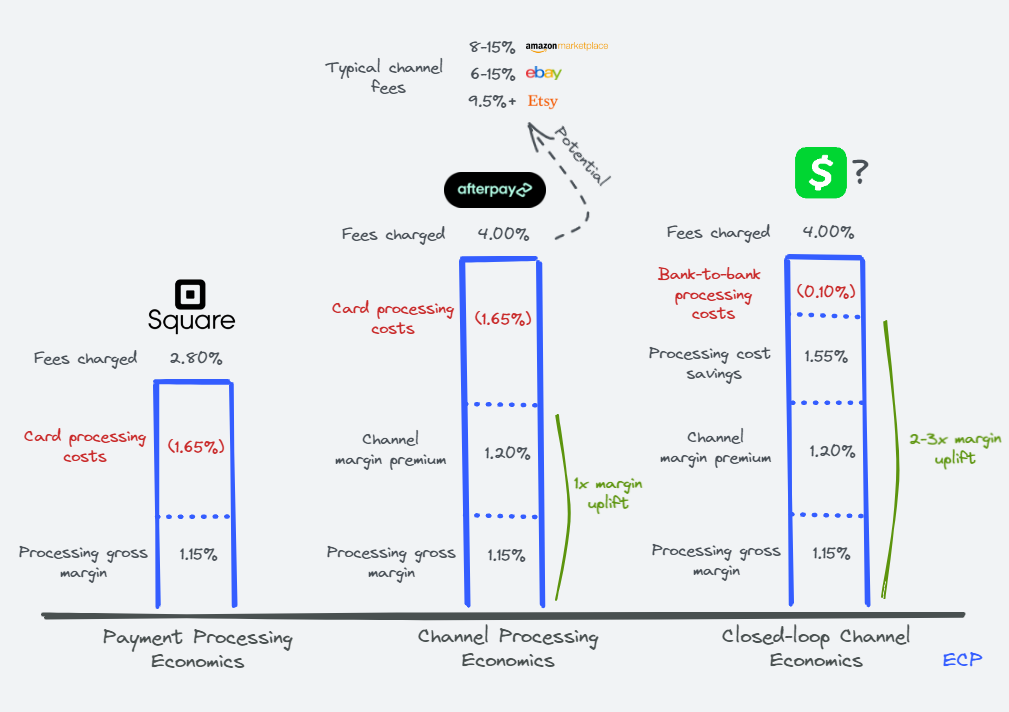

Traditional payment processing fees range from below 1% to almost 3%, depending on the size of the merchant (among other factors). In Cash App Commerce, it's reasonable to believe that channel fees could be negotiated as high as 3% for enterprise merchants and above 5% for SMEs. Today, many established eCommerce marketplaces cite channel fees between 8-15% depending on the product category.

Add to this the potential cost benefits. PayPal (and Afterpay) network models are relatively disadvantaged compared to Cash App in that consumers (often) don't hold excess funds within the app. Instead, at the time of purchase, PayPal needs to initiate a pull transaction through the customer's linked debit or credit card. In less regulated interchange markets like the US, this usually costs 1-2% of the value of the pulled funds. Given PayPal generally charges merchants processing fees of 2.9%, this funding cost is a material margin leakage.

In contrast, Cash App acts as the consumer's bank, and Commerce creates a direct connection between the merchants and consumer for a bank-to-bank money transfer which cuts interchange out of the cost equation.

Putting this together, gross margins can expand from 1% of the transaction value to upwards of 3% in a closed-loop transaction, with the benefit of a channel premium - illustrated below.

If Block can aggregate consumer demand and charge merchants channel fees, it will create a financial resource from which it can share the economic benefit with its consumers, increasing the reason to shop within Commerce and speeding up the coveted flywheel whereby increasing consumer spend increases the propensity for merchants to participate in the network.

To kickstart that flywheel, we expect Block to first tap into the Afterpay enterprise merchant base, signing up big-name retailers and leveraging Afterpay's co-marketing playbook to draw consumer demand. Thereafter, Block is likely to actively advertise the Commerce opportunity within Cash App to its existing commercial relationship with thousands of Afterpay SME merchants. If successful, it could emerge with a scaled network at an impressive speed.

The network opportunity could also extend beyond eCommerce to offline retail. Block recently updated a patent for 'generating multi-merchant loyalty programs' based on complementary services and geographic thresholds, where consumers can be 'dynamically enrolled' and receive incentives to conduct transactions with the merchants in the program. With this patent, it's conceivable that Cash App could bring a map interface into Commerce, giving consumers visibility into existing Square merchants - and loyalty programs - relevant to their location or registered address. Doing so would give the millions of Square merchants an opportunity to participate in the network as well.

Reason #2: Personalised Commerce

A critical challenge faced by all marketplaces is serving consumers with relevant content. Understanding a consumer's shopping interests requires a historical profile. Without it, relevance and value-add are hard to achieve and risk dwindling interest.

While search functionality allows marketplaces to build a consumer's demand profile over time, a longer history of a consumer's transaction activity could build a richer picture. Luckily, Cash App is increasingly serving as an active user's main bank account.

Although privacy laws would prohibit consumer data from being shared with merchants, Block could leverage its consumer insights informed by bank transaction histories to surface relevant content from merchants in the Commerce interface, and initiate a centrally managed target marketing platform for merchants. Effectively akin to what Amazon Marketplace does today, but with the added richness of a detailed financial profile of the customer.

We would expect personalisation to extend beyond what to buy, to also incorporate the when and how, based on knowledge of a consumer's payroll (direct deposit patterns), credit liabilities (upcoming repayments), and keeping in line with Block's vision of financial empowerment - helping consumers remain financially responsible.

Other lessons about personalisation innovation can be drawn from Chinese marketplaces where features such as direct in-app communication with merchants, live product shows, or social commerce are becoming mainstream consumer experiences.

For merchants, Cash App could attempt to follow WeChat's mini-apps innovation - merchant-developed interfaces within the master Commerce interface that gives customers a uniquely curated shopping experience and helps retailers reach targeted audiences. WeChat's mini-app programs launched in 2017 and recently passed 600 million daily active users.

A Potential Third Reason? An opportunity to redefine FICO

As we pontificate about what's possible when commerce and banking are intertwined by a company with a vision of financial access, empowerment and redefining the relationship with money, a lot of ideas come to mind.

In the first piece of our series on Block, we wrote about how Square did away with traditional fraud prevention models and utilised innovative data science tools to reduce risk and approve small merchants with thin operating histories.

We see the same opportunity ahead for Cash App and its approach to consumer credit. By creating its own version of FICO, Cash App could give underserved consumers the ability to build their proprietary credit score within the Cash App ecosystem, beginning at the inception of their financial life and starting with small amounts of credit.

Moreover, Cash App could progressively increase credit allowances to top-ranked consumers based on their score, allowing them to move up the credit curve from Cash App Borrow and BNPL to larger-scale student loans, vehicle finance, and ultimately mortgages.

The ability to build an in-house credit profile that's more accessible than the existing FICO system, would likely add a long-term form of consumer loyalty (to grow the score) and reduce risky credit behaviour (to maintain a good score). Meanwhile, this could expand Commerce into higher-value verticals.

Conclusion

We believe Cash App's Commerce vision is to create a financial hub where consumers can access highly personalised commerce, which draws upon the best retail offers, layers on loyalty rewards, and provides the necessary financial tools for consumers to participate and make a financial difference in their lives.

This is not to say the vision will be easily achieved: execution, competitive forces and regulatory changes will be substantial hurdles to overcome. The opportunity exists to move consumer finance to the top of the commerce funnel, but it is over to Block to achieve it.

The article has been prepared by ECP Asset Management Pty Ltd (ECP). ECP is a funds management firm based in Sydney, Australia. For further information, visit www.ecpam.com. ECP and the author own shares in Block (ASX: SQ2). This material has been prepared for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide and should not be relied on for financial advice. ABN 26 158 827 582, AFSL 421704, CAR 44198.